Challenge Breeds Stability

It's almost a given in the tech industry any more that you have to change jobs every few years. For one thing, getting a new job seems to be the only way to get a substantial pay raise rather than the typical yearly 1-3%. (Disclaimer: I've never worked for a Silicon Valley company so I don't know the first thing about working out there...) And the truth is, especially in the first 5-10 years of your careeer in tech, chances are pretty good that you deserve one or two 15-20% raises because if you've survived that long then you've probably progressed from a micro-managed spec-follower to someone capable of making your own design decisions and at least contributing to the plan.

This march I will have been working for AlumnIQ for 8 consecutive years. Eight! Not only is that uncommon in general, it's also uncommon based on my personal history. My post-college tech jobs have lasted, in chronological order: 3 years, 3 years, 3 years, and now 8+ years with no end in sight.

What's different?

Throughout my career the type of work I've done has been pretty constant: always trending toward more web-dev, and mostly using the same technologies.

As a young dev I learned to love creating admin-areas. I think this was in part because I wasn't any good at web design, so by focusing more on CRUD forms in an area where the design wasn't as important, I got to feel productive and get stuff done. Eventually I tired of creating CRUD forms over and over and over, though. You can only do so many of them before you have dealt with every possible problem and you're just over it.

My first job was working in IT at a big food company, mostly writing mainframe code to integrate accounts payable and accounts receivable with external systems, but occasionally getting to do some web-dev. After 3 years I left that job to take my second job because it would give me a better opportunity to focus on the tech stack I wanted to be using, and it certainly didn't hurt that it came with a big raise.

My second job was working at a small consultancy (~50 people), on my favorite tech-stack of the time. My manager there opened my eyes to the world of tech blogging and tech conferences. Seeing his articles in trade magazines inspired me to start blogging and attending conferences. With his mentorship, I think this is when I started to grow from some young punk capable of writing CRUD forms into the beginnings of a "senior" developer by some reasonable standard. I started to understand the bigger picture. I was occasionally asked to be interim team lead when the PM was on vacation. I was tasked with many process improvements and initiated things like source control usage (not that our consultancy didn't use any, but some clients didn't), local dev environments, code reviews, and code generators/orm.

(Hey Chuck, thanks for everything!)

After I had been there for about 3 years that company was sold to a larger international consultancy, and slowly but surely our office started to empty out as people were unhappy with the new parent company. The writing was on the wall: the ship was sinking and I needed to find a new home. But by this time I had roots. I got married only a few months before moving to Pennsylvania to take job #2, and by now we had our first kid. Moving wouldn't be as easy any more. So a big part of what influenced my next job selection was local availability.

I ended up finding my next job through Twitter, of all things. One afternoon I met up for drinks with someone I knew casually through tech circles, and eventually the conversation turned to job availability at his company. I ended up getting that job and working there for another 3 years. It was a different job: Still a lot of CRUD forms, but in a different context. We made "simulations and serious games" to let university students experience business concepts for themselves. I got to meet some NFL players and big-shot corporate executives, and working on games made it a novel experience. I decided it was time to go when I could see a tech stack change mandate coming from management, and knew I would hate the new stack.

By this point I had been attending some tech meetups and become friends with Steve. When I decided it was time to leave the university, we started talking about working together. At the time he was solo consulting, but he had big ideas to pivot into products in the university-sports and alumni-engagement verticals. We consulted together for a while to build up some cash reserves and make some strategic customer partnerships, and then jumped into the product world. The sports product ended up not working out and we shut it down, but our engagement products are going gangbusters.

And then all of a sudden, overnight, 8 years went by.

What happened? We found success in products.

We found a pain point that customers were willing to pay to fix, with tremendous room for improvement, in a relatively under-served market. We're still small compared to our competition, but even so, our customers are our biggest champions and we regularly get nice emails letting us know that they saw us hyped in a trade-conference presentation or that our existing customers just talk us up so much that they had to find out if the hype was real.

This kind of success brings its own challenges.

We had done a decent job of following the age-old advice of not prematurely-optimizing, using what we knew, building fast and iterating to find the best path forward.

Now, we've got a product that our customers love, that we have data to prove is making them more profitable and efficient, and that even more people want to buy. In a word, our new problem is scaling.

Scaling

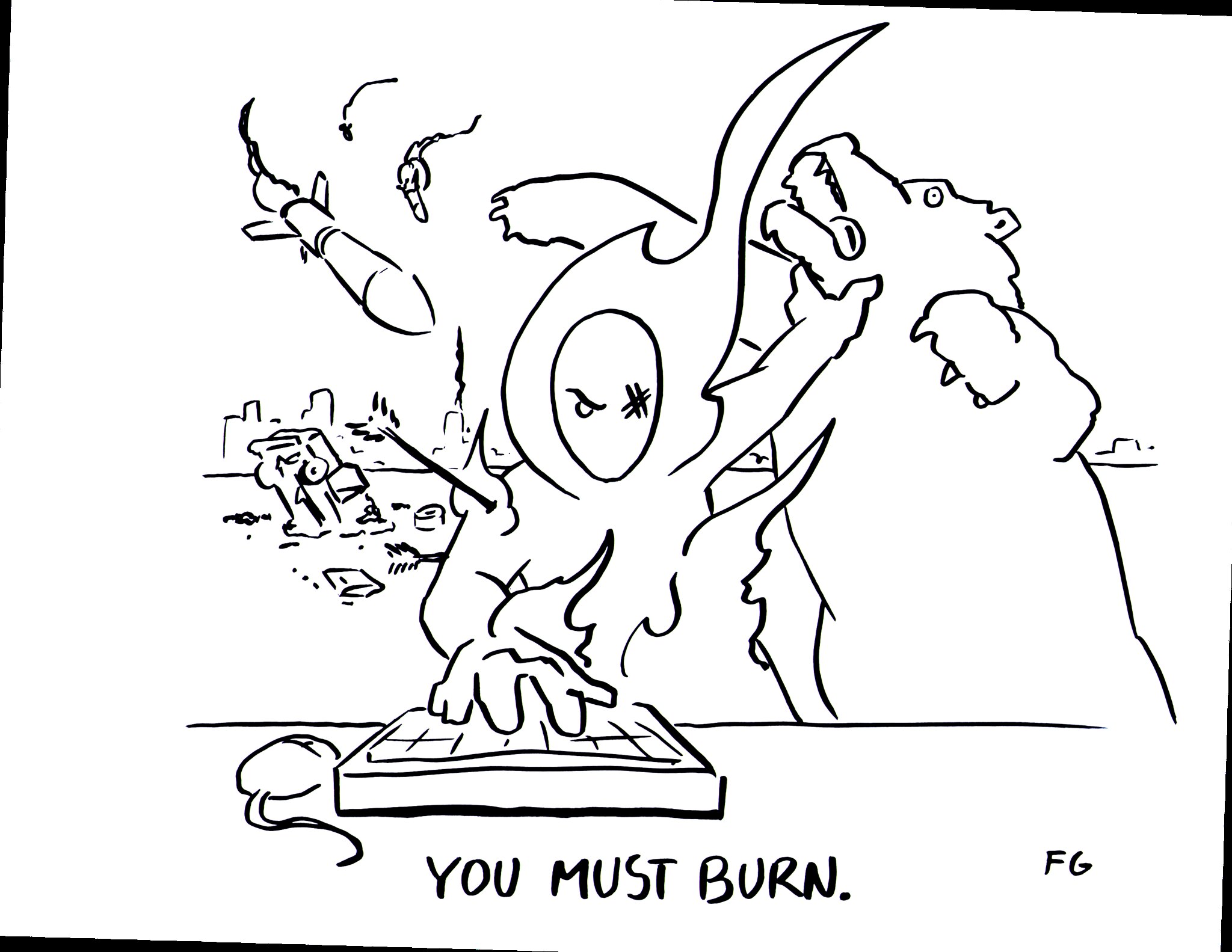

This is a whole new world. No longer do we get to revel in making the best possible CRUD form. Now we get to deal with challenges like: Sending 1,500 emails per hour isn't fast enough. It's too much work to create an environment to bring new customers online. Deploys are too manual and fragile. And, sadly, our tech stack is a little outdated and that's starting to make things difficult. It served us well in getting here, but it's time to Marie Condo it: Thank it for its service, and then put it in the trash pile, one stained and tattered t-shirt at a time.

So we refactored that email process out of our monolithic app into a sort of microservice utilizing, among other things, some serverless tech, and now we have to self-throttle down to 1,500 emails per minute to prevent DDoS'ing our mail provider.

We're working on containerizing, scripting, and automating deploys.

And we're taking steps to modernize our tech stack. Even with a team of just a couple of developers, we've managed to amass a large product over the last ~6.5 years. You don't just rewrite that all at once and flip a switch. We're being slow and methodical and trying to keep modernization on track while also continuing to expand and improve our product.

It's challenging, and that's a big part of why I no longer get cabin fever even though I've been working from home for 8+ years; and why I am usually excited to get back to work every day.

What's next?

It feels like we've ascended. Similar to Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, we've satisfied our ability to survive: we know that our core functionality is useful and resilient, and now we get to focus our energy on some things that make our lives better and enable us to operate at a wider scale with our small, remote team: more-modern tools, developer experience, and operations automations.

I don't know what existence will be like on the plane above this one, but my goal for the year 2030 is to get there and find out.