The Flywheel of Testing

Tags: #learning in public, #testing

On my continuing quest to get better at testing, I have spent quite a lot of time in the last couple of weeks reading about testing, watching tutorial videos, and practicing testing in my work. It has been a long, slow, difficult, slog. I'm not sure what made me think of it, but I was reminded of a flywheel.

If you're not familiar, a flywheel uses its inertia (the conservation of angular momentum) to store energy. There are flywheels in ICE cars, childrens toys, and thousands of industrial machines. They are all around us. The dimensions and mass of the flywheel determine the energy needed to get it spinning and up to a useful speed, but once it's there it helps even out any fluctuation in pace.

So too (I am learning) with testing

I believe that if not already fully, I am *this close* to a complete understanding of the fundamentals of testing. As concepts, I grok pure functions, side effects, isolation, dependency injection, and mocking.

What I don't fully grok yet is the tools I'm using to put this understanding to useful implementation. I am not exactly proud of the test code I've been writing this week. It's a mess.

But it works.

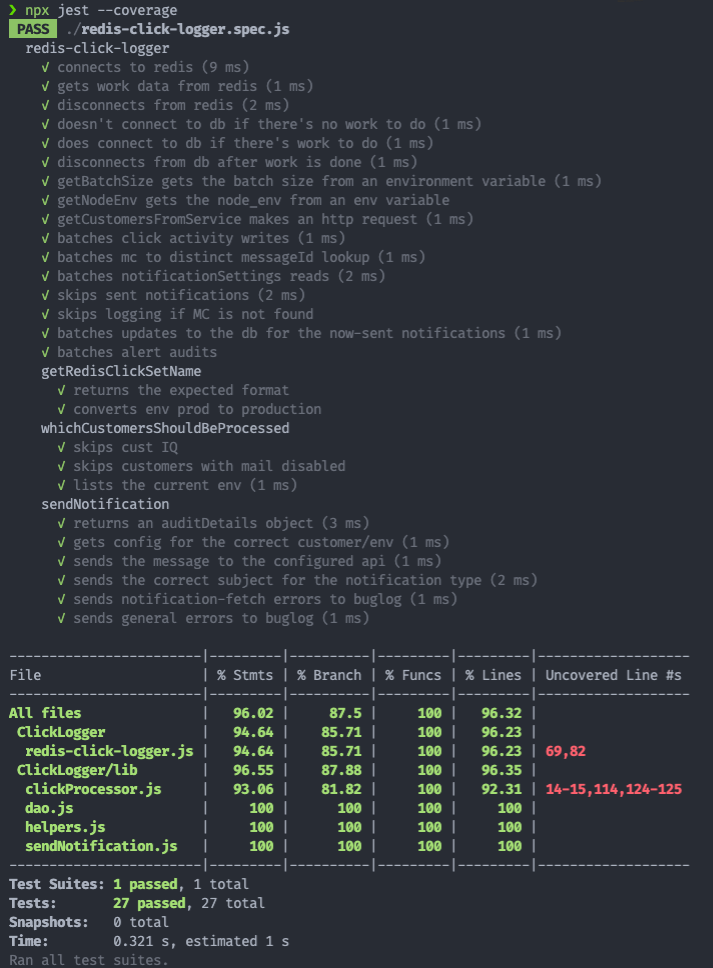

That's 100% passing tests with more than 96% code coverage overall. And I believe I'm going to hit 100% very soon.

I'm proud that it exists. I'm proud that it does its job. I would never dream of sharing the test code as an example of how anyone should write tests. Well, maybe just to show that it's OK to do a bad job on your first draft. Just like writing research papers in school, and just like writing our application logic, it doesn't have to be perfect in your first draft.

The practice of "write & refactor & write & refactor & write & refactor & ..." is well ingrained in me when it comes to prose. I use it with my blog articles, emails, even the terrible fiction I occasionally write that will never see the light of day. I find it really helpful to be able to get an idea out of my head and in front of my eyes without worrying so much about grammar and clarity. It's a lot easier to refactor an existing sentence to use proper grammar and to be more clear than it is to divine a perfect sentence without ever putting (metaphorical) pen to paper.

Some of the code I write today comes out pretty decently formed on the first try, but only for languages that I've been using ~daily for ~decades, and even then, only in certain contexts.

If testing has a flywheel, and I say that it does, the energy it consumes to get up to speed is donated by your doing a bad job writing tests, but writing them anyway. Write them, make them useful, then purposefully inspect them and think about how to make them better. It's going to take longer than it should, at first. Like, way longer. That's ok. It's worth it. Just as our code needs some cycles of write & refactor, so too do our tests.

Mine do, at least.

Just as perpetual motion machines don't exist, getting your testing flywheel up to speed doesn't mean it will generate free tests into perpetuity with zero effort. The job of the flywheel is to slow the draining of energy from the system, and to smooth out any unevenness in inputs. If your testing flywheel is fully up to speed and you take 2 weeks of vacation from work, there's a good chance you're going to come back and be able to get right back to work without much effort to get back into the rhythm.

The inverse is also true: If your flywheel is only barely moving before you take that same 2 weeks of vacation, coming back there's a much higher likelihood that your flywheel has slowed to a complete stop and you're going to have to start over.

If you have the time, open source projects (even if they aren't likely to be put to use) are a great low-risk opportunity to learn new techniques and tools. Write a blackjack game, and use it to learn to write tests. It won't matter if you get stuck because nobody is depending on your blackjack game, and when you do figure it out you'll have new skills you can put to use at your day job.

Don't expect testing to be something you decide to start doing and instantly find yourself able to do up to even your own meager standards. Getting that flywheel moving takes time. Lots of it.

And you know unclean code when you see it. That's what makes it hurt on the inside, and I bet it's what turns a lot of would-be testers away. They couldn't push through the pain of having to write bad tests so that they could learn to write good tests.

Plan for that extra time and effort when you start to implement testing in your work. But also expect that it gets easier if you keep going. Eventually you should start to see its benefits and the inertia stored in your testing flywheel will help you keep that testing momentum smooth and even.

Write & refactor & write & refactor & write & refactor & ...